FOOTPRINT OF FOOD

Our carbon footprint measures how much carbon dioxide equivalent gas we emit into the atmosphere. If we all reduced that to zero, then we would have much less of a problem with climate change.

Food is a large source of the carbon we create through our consumption. It is around 20% of the total footprint in Shropshire at 3.6 tonnes CO2eq.

Calculating the carbon footprint of food can be very complicated because it needs to consider how much of the different gases are emitted as part of the whole process of producing an item of food.

Let’s take a simple food item like milk. Cows waste a lot of energy from their food (grass, silage, etc.). Cows ruminate (chew the cud) which means that they burp up methane, which is a very damaging gas. If they are fed on soya, there may have been a deforestation element that went on to create the soya farms. On top of that we need to consider the activities of transporting the milk from farm to supermarket, the packaging, and refrigeration, which also contribute to your carbon footprint. A litre of milk creates a footprint of 2 kg CO2 equivalent. So if your household drinks a litre a day, you will emit nearly a tonne of CO2 eq. (which, to put it in some kind of context, is almost equal to a flight from London to New York).

This calculation is based on production in the UK.

A 250g pack of Asparagus is another example of the issues behind the food. If you buy it locally and seasonally, then the footprint is “only” 270g of CO2eq. But if the same pack is airfreighted from Peru, the impact of flying it takes the footprint to 4.7kg CO2eq. Hence we must be really careful about where our food comes from and how it gets to us!

You may wonder where this information comes from. One day we may all get the government to label foods with their carbon footprint, so we can check when we buy in the same way we can check fat content or sugar content today. But that is likely to take an age, as they try and agree on standard units, how to display them, and then get manufacturers to change their packaging.

In the meantime, there is a great book by Mike Berners-Lee called “How bad are bananas?” This sets out the carbon footprint of almost everything you might eat and a lot more besides. You may think it is not quite as interesting as a racy rom-com or a thrilling spy novel, but there is a lot of fascinating information in there.

IS VEGANISM GOOD?

From the example above, we can see that eating beef will not likely be good. In fact, an 8oz steak from deforested land in Brazil causes 17.8kg of CO2 eq. So if we had steak once a week, we would emit nearly a tonne of CO2 eq. So we could stop eating meat and replace it with just a plant-based diet.

A research study (by P Scarborough et al. in 2014) compared the amount of Carbon Dioxide emitted due to the diets of different types of “eaters”. Thus it broadly compared meat-eaters with vegans. A simple graphic illustrates the difference.

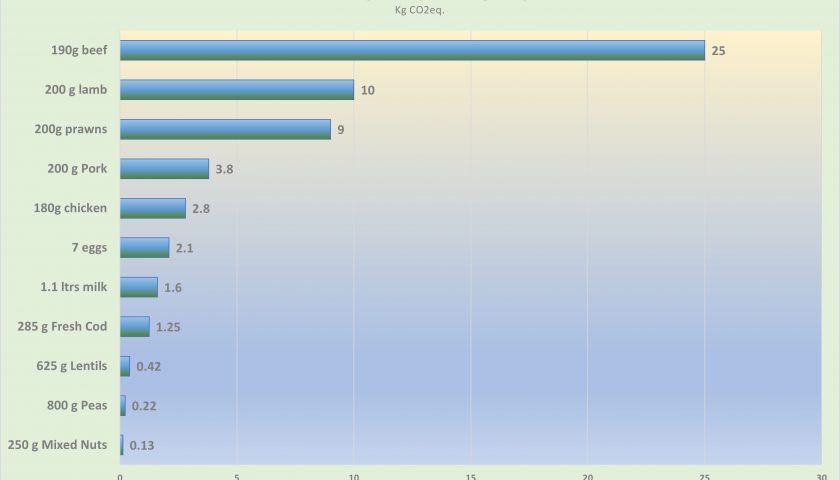

Thus by switching to being vegan, then you will be more than halving your emission of consumption from (some of your) food. If you look further into this and determine how much your footprint is based on a need for an average of 50g of protein per day, you will see how much benefit you can get from eating more of a plant-based diet. The following chart lists out various foods you could choose to eat and the amount of CO2eq you will emit in the process:

Hence a plant-based diet is better for the planet. But we also need to be a bit careful because if we all moved to a fish-based diet, we might run the risk of running out of responsibly caught cod. So a balanced diet is good.

In schools, Local Authorities can change the diet served to ensure it is nutritious but better for carbon dioxide emissions. For instance, since 2009, Bristol City Council has moved to a situation where 45 % of the food is made from locally sourced food and 30 % is prepared with organic produce.

SIMPLE ACTIONS

As you can see from the above information on the emissions of CO2 type gases from different types of food, then the situation is complicated. But there are simple things you can do to change your diet to make your lifestyle more friendly to the planet.

Meat and dairy products

We can see from above that the consumption of beef causes problems with the atmosphere as “ruminants” belch methane, which environmentally is a very toxic greenhouse gas. The type of farming involved also has an impact. Farms which are exclusively managed for the production of beef are worse than those which are also geared to produce dairy products, as dairy is proportionately less of a problem for the generation of Greenhouse Gases. In addition, in Shropshire we have around 3,500 farms and around 60 % are grassland. So we have a significant business in the production of meat (as we do across the UK).

We can see that beef produced in places like Brazil, Argentina, and other countries also causes further carbon emissions across the supply chain as they are transported to their markets. Local farming practices in these countries also lead to deforestation which removes an important method for capturing Carbon Dioxide.

We can also replace the milk we drink with Almond or soya milk and replace dairy butter with plant-based alternatives.

So a responsible attitude to our diet, if we want to continue to eat meat, is to eat local (check the labels ) and eat meat that is produced responsibly. Meanwhile farmers themselves aer changing the way they farm to take into account the impact on the environment. Some in Shropshire have also turned muck into money, by converting manure through a process called anaerobic digestion into electricity, and exporting that into the grid. Some have invested in solar farms and allow sheep to graze in and around the panels.

Shop locally and seasonally

As we can see from the above explanation on our Carbon Footprint, buying lettuces and strawberries grown in Spain will cause carbon emissions as they are transported by trucks or planes across Europe to your local supermarket. So if you shop for fruit and vegetables when grown in season in the UK, you will be supporting UK agriculture and helping to reduce carbon emissions.

So when you are shopping, check the labels for the source of the product, and if it’s asparagus grown in the UK, and you want asparagus, then buy it. But if its Asparagus grown in Peru, put it back on the shelf! Do join in to encourage supermarkets to label their foods so we can know where they come from!

You can also help our local farmers and markets by buying in

- Farmers markets

- Farm Shops

- Shops that sell local food, fruit and vegetables

- Food festivals (for instance Ludlow (September 2022) and Shrewsbury (June 2022))

EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet

EAT is a global, non-profit startup dedicated to transforming our global food system through sound science, impatient disruption and novel partnerships. They observe that:

- Healthy and sustainable food can be a powerful driver of change: The EAT-Lancet Commission outlines a planetary health diet, which is flexible and recommends intake levels of various food groups that we can adapt to our local geography, culinary traditions and personal preferences. By choosing this diet, we can drive demand for the right foods and send clear market signals all the way through the food value chain back to the farmers.

- A diet that includes more plant-based foods and fewer animal-source foods is healthy, sustainable, and good for both people and the planet.

- Plants provide protein. Aim to consume at least 125 grams of dry beans, lentils, peas and other nuts or legumes per day.

- Go easy on meat. Aim to consume no more than 98 grams of red meat (pork, beef or lamb), 203 grams of poultry and 196 grams of fish per week.

- Less is more. Consuming too much food can lead to weight gain and other health problems and it is also a challenge for the environment. Taking the time to share meals with family and friends and choosing single-serving portions are two simple ways to avoid eating more than we need.

- Plan the week ahead. Healthy and sustainable eating can be tasty, flexible and dynamic. Plan menus for the coming week to ensure a diversity of delicious dishes and shop according to plan. This will also save time and money and help reduce waste.

- Waste not, want not. Packing leftovers into lunch boxes, using them in new creative recipes or keeping them for future consumption is good for the planet and for your budget. With less food waste, less food needs to be produced to feed the world and the planet can be spared.

Click on the following link to go to the source website for further information.

Grow your own

You may have enough space to grow some fruit and vegetables in your garden. If not, there might be an allotment you can find near you, where you can grow your own. It takes some time and effort to grow onions, lettuces, carrots and so on. But you could find it very satisfying eating your own fruit and vegetables while helping the reduction of carbon dioxide.

Many people cannot grow their own, so finding and cultivating an allotment might be a good idea. You can find about local allotment associations in Shropshire on this website:

There are lots of excellent resources online to help you grow your own food. You’ll find guides and how-to videos on preparing your soil, pest control and growing specific fruit and vegetables. For instance go to the Royal Horticultural Society Website. It tells you what to do, when to do it, and how to grow your own:

SHROPSHIRE GOOD FOOD PARTNERSHIP

In Shropshire, we have a CIC called the Good Food Partnership. Their vision is to help create regenerative food, farming and land-use systems. Its mission is to bring people together to create a local food system which is good for people, place and the planet. They support the work of organisations across the county, catalyse new initiatives and collaborations, and enable joined-up innovative thinking to improve access to good food and reimagine land stewardship.

They have produced a “Good Food Charter” which we show here:

You can join in with the partnership by clicking in on the following button: